A Century of Stewardship

The history of conservation in Etosha National Park

Photographs Louis Wessels

From the Winter 2025 issue

Etosha National Park, often called the “Great White Place” due to its enormous salt pan, is not only one of Namibia’s top tourism destinations; it is also one of the oldest and most iconic conservation areas in Africa. Its story is one of resilience, transformation and an evolving understanding of what it means to protect nature for future generations.

BEGINNINGS IN A COLONIAL ERA

The formal conservation journey of Etosha began on 22 March 1907, when Friedrich von Lindequist, the then governor of German South West Africa, proclaimed the area a Game Reserve No. 2 under Ordinance 88. The reserve originally covered 100,000 km 2 , stretching from the Kunene River in the north to the Omuramba Ovambo in the south – an area that, at the time, was one of the largest conservation areas in the world.

The goal was to protect the dwindling numbers of large game species that were being heavily hunted by settlers and traders. However, the size and management of the reserve would change significantly in the decades to come.

SHRINKING BORDERS, GROWING INTENT

By the mid-20th century, Etosha’s boundaries were gradually reduced due to pressure from farming, mining and settlement expansion. By 1970, the park had been reduced to its current size of approximately 22,912 km 2 – still vast, but a fraction of its original extent.

In 1967, the area was officially renamed “Etosha National Park” under South African administration. Despite these changes, Etosha’s core value remained: to safeguard the biodiversity of the north-central savannah and salt pan ecosystems.

ECOLOGICAL SIGNIFICANCE

Etosha is home to over 114 mammal species, 340 bird species and more than 100 reptile species, including several that are endemic or near-endemic to the region. The stark contrast of its saline pan, mopane woodland and grassy plains create an ecological mosaic where highly adapted species thrive.

ENDEMIC AND NOTABLE SPECIES

- Black-faced Impala (Aepyceros melampus petersi): Found almost exclusively in north-western Namibia and south-western Angola, this subspecies is distinguished by its darker facial markings. Etosha provides a vital sanctuary for this rare antelope, which was once under severe threat due to hybridisation and habitat loss.

- Hartmann’s Mountain Zebra (Equus zebra hartmannae): While not endemic to Etosha specifically, this subspecies is unique to Namibia’s mountainous regions and is sometimes spotted in the western parts of the park, especially around Dolomite Camp.

- Damara Dik-Dik (Madoqua kirkii damarensis): A subspecies of the Kirk’s dik-dik, this tiny antelope is endemic to Namibia and southern Angola. It thrives in Etosha’s dry thorn scrub, often found in monogamous pairs.

- Etosha Agama (Agama etoshae): A lesser-known but fascinating reptile, this lizard species is endemic to the Etosha Pan region.

- Blue Crane (Anthropoides paradiseus): Namibia’s population of these elegant birds is extremely small, and Etosha remains one of the few places where they still breed.

A HAVEN FOR LARGE MAMMALS

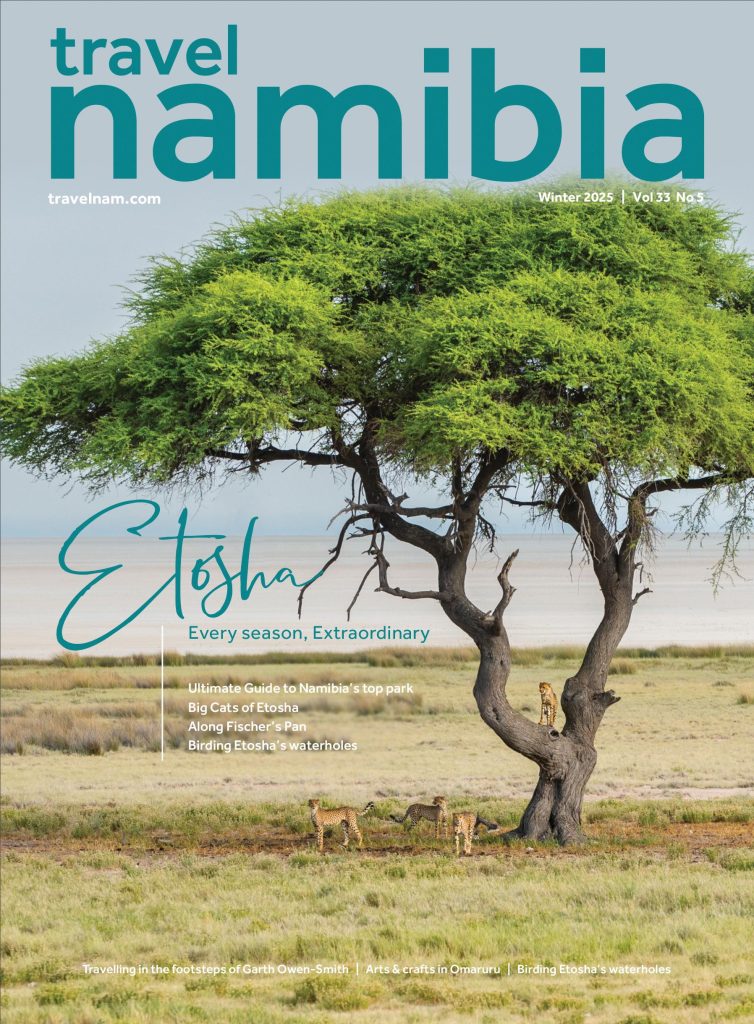

Etosha is one of the best places in Africa to see the black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis bicornis) in the wild. Thanks to decades of anti-poaching efforts and tight surveillance, Etosha has maintained one of the strongest populations of this critically endangered species, though the reality and continued threat of poaching remain prevalent. The park also houses healthy numbers of African elephants, lions, spotted hyenas, leopards and cheetahs, alongside diverse herbivores such as springbok, gemsbok, kudu and blue wildebeest.

The park’s numerous artificial and natural waterholes play a pivotal role in its conservation model, providing essential hydration during the long dry months and offering visitors some of the best wildlife-viewing opportunities on the continent.

MILESTONES IN CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT

1974–1980: Operation Noah’s Ark

As wildlife populations dwindled due to recurring droughts and overgrazing, a major restocking programme was launched. Dozens of species were relocated within the park to re-establish balance. This period also saw the development of boreholes and improved infrastructure.

1990: Namibian Independence

Etosha entered a new phase of conservation guided by Namibia’s constitution – one of the first in the world to include environmental protection (Article 95). Management began to focus more on community involvement and scientific monitoring.

2000s–present: Facing the 21st century

A growing emphasis on the use of technology in anti- poaching and research collaborations has helped Etosha adapt to modern-day conservation challenges.

THREATS AND CHALLENGES

Despite its successes, Etosha still faces major challenges, including poaching, climate variability and human-wildlife conflict on its periphery. Conservationists also monitor the risk of disease transmission, particularly from livestock in buffer zones.

Continued funding, research and responsible tourism are vital. Visitors contribute not only through park fees but also by supporting the broader ecosystem of conservation- based employment and awareness.

A LEGACY TO PROTECT

Today, Etosha stands not just as a symbol of Namibia’s natural heritage, but also as a living example of how conservation has evolved, from fortress-style protectionism to integrated, ecosystem-based stewardship.

As you watch a lion yawn beneath a tree or see a flock of flamingos ripple across the shimmering pan after rare summer rains, know this: Etosha is what it is because people chose to protect it… and must continue to do so. TN