Droombos Estate

Just minutes from Windhoek and yet worlds away from its pace, Droombos Estate has become synonymous with refined hospitality and

where red dunes meet wandering rivers

Text ANJA DENKER | Photographs ANJA DENKER

The word Kgalagadi is derived from kgala, meaning “to dry up” or “to thirst”, and gadi, meaning “place of”. Together, Kgalagadi describes the vast semi-desert region stretching across Botswana, South Africa and partly bordering on Namibia – a landscape defined by red dunes, ephemeral rivers and an enduring scarcity of surface water; a land of thirst. Much has been written about the Kgalagadi: home of ancient hunter-gatherers, a vast wilderness and a land of silence and survival. For thousands of years, the San and later the Khoikhoi roamed the Kgalagadi’s red dunes and dry riverbeds, living in harmony with its harsh beauty. Their ancient tracks, stories and rock art mark the desert as one of humanity’s oldest homelands.

With the arrival of settlers in the late 19th and early 20th century, cattle, farming and hunting was introduced and wildlife declined. This led to the proclamation of the Kalahari Gemsbok National Park in 1931 under the stewardship of Johannes le Riche and his assistant Gert Jannewarie. Across the border, Botswana established the adjoining Gemsbok National Park in 1938. Decades later, these two wilderness areas were united to form the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park in 2000 – Southern Africa’s first peace park, celebrating shared heritage, open landscapes and cross-border conservation.

The historic !Ae!Hai Kalahari Heritage Park land settlement agreement with the government of South Africa saw six farms (totalling around 35,000 ha) to the south of the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, and nearly 60,000 ha of land within the park, restored to the Khomani San and Mier communities in 2002.

There are three main entrance gates: Twee Rivieren in South Africa, Mata-Mata in Namibia, and Mabuasehube in Botswana. Two additional gates in Botswana (Two Rivers and Kaa) allow access to the park, but the primary entrances are Twee Rivieren, Mata-Mata, and Mabuasehube.

Travelling from Namibia, there are beautiful places to explore along the way. The quaint town of Stampriet, a small agricultural centre sustained by the underground waters of the Stampriet Artesian Basin, has an intriguing historical past and produces an array of fresh fruits and vegetables. Both Gondwana’s Kalahari Anib Lodge and the charming Kalahari Farmhouse at Stampriet make for inviting stopovers to unwind before entering some truly remarkable scenery, with the gravel road winding through the Auob riverbed. Lined with majestic camelthorn trees and a glimpse of red dunes in the distance, this stretch offers a first taste of the Kalahari’s stark beauty

Despite the harsh conditions, game viewing is exceptional, as wildlife is more concentrated in the dry Kgalagadi.

The park conserves one of the world’s most abundant semi-arid biomes. The southern and western areas are dominated by Kalahari xeric savanna, interspersed with acacia-baikiaea woodlands. As is typical in arid regions, the weather can be extreme: midsummer days in January often exceed 40 °C, while winter nights drop below freezing. Recorded extremes range from -11 °C to 45 °C, and rainfall is sparse.

Vegetation is sparse but hardy, including deep-rooted acacias and other drought-resistant plants. The tsamma melon, African horned cucumber and the devil’s claw thrive here and a variety of wildflowers provide brilliant specks of colour, especially after the rains. Despite the harsh conditions, game viewing is exceptional, as wildlife is more concentrated in the dry Kgalagadi.

The park is home to more than 55 mammal species, making it a haven for predator enthusiasts. Iconic carnivores include black-maned Kalahari lions, cheetahs, leopards and hyenas, while migratory herbivores such as blue wildebeest, springbok, eland and red hartebeest traverse the park in impressive numbers. Smaller residents include meerkats, ground squirrels, honey badgers, pangolins, Cape foxes and bat-eared foxes. Meerkats, Cape foxes and bat-eared foxes often have dens close to the roadside and many happy hours can be spent observing family life around the den, especially when youngsters are around, providing endless entertainment with their antics.

The park’s birdlife is equally remarkable, with over 260 species recorded, including an astonishing diversity of raptors. At least six species of owls can be seen, among them Verreaux’s Eagle-owl, Spotted Eagle-owl, White-faced Owl, African Scops Owl, Pearl-spotted Owlet and Barn Owl. Having visited the park an estimated fifteen times since 2011, it was probably the sight of a spectacular blackmaned Kalahari lion that sparked my enduring love affair with the Kgalagadi. Watching any of the large, charismatic cats gliding across red sand, or ambling slowly along the deep, sandy tracks of the Auob or Nossob riverbeds, is enough to send your pulse racing. The park is also one of the best places to spot the striking African wildcat, often glimpsed at close range, well concealed in the camelthorn and grey camelthorn trees lining the riverbeds. Sightings of the more elusive caracal are not unusual, with many memorable encounters captured in photographs.

Even though the sight of giraffe navigating the dune-scape along the Auob feels wonderfully incongruous, it is a reminder of the Kgalagadi’s surprising diversity. The Auob Valley has often set the stage for spectacular cheetah chases. Herds of springbok frequently gather here, attracting the world’s fastest cat into striking range and offering nail-biting moments when the chase begins, culminating in a blur of speed, dust and raw wilderness drama.

Life in the park centres around its many waterholes, scattered along the Auob and Nossob riverbeds. Yet wildlife – especially the predators – rarely linger, and sightings are often a matter of pure luck, which makes each encounter all the more rewarding and thrilling. Setting out at first light, with sharpened senses and high expectations, is often most productive, particularly for lion and leopard sightings. The predominantly nocturnal brown hyena is also frequently on the move at this time of the day, providing a rare opportunity to observe these elusive, shy creatures up close. Photographers treasure the golden hours – that magical glow of early morning or the soft rays of the setting sun – when a hint of dust in the air turns every scene into a work of art. Wildlife encounters are often unusual and spectacular, from a feisty jackal nipping at the heels of a brown hyena to aerial combats between raptors, a leopard enjoying the shade of a car, noisy and terrifying lion brawls when young males are ousted from the pride or the tender birth of a springbok lamb.

The park has three main camps: Mata-Mata, Twee Rivieren and Nossob, each with a waterhole, chalets, campsites, a fuel station and wellstocked shops. Yet for me, the real magic lies in the six wilderness camps scattered throughout the park – wild, unfenced and intimate. Four selfcatering chalets sleep two, except for the larger Kalahari Tented Camp, which also offers family units. Picture yourself on your stoep, overlooking the waterhole, G&T in hand, the fire casting a golden glow over the bush, lions wandering nearby and the sounds of barking geckos all around – classical Kalahari!

Even the mischievous lions add their own charm, chewing car tyres and listening in fascination to the hiss of air escaping the punctures, which at times had left guests stranded until replacement tyres arrived from Upington! SANParks, ever resourceful, solved the problem with clever metal cages that go around the tyres, keeping the wildlife entertained but the vehicles safe.

For me, the lure of the Kgalagadi lies not only in its predator-rich environment, but in the sum of its wholeness – the red dunes, dust and dreams, the golden light, whispers of wind and wilderness, vast skies, spectacular thunderstorms, tales of hardship and endurance, footprints in the sand and that profound sense of peace and solitude that settles over everything. TN

Just minutes from Windhoek and yet worlds away from its pace, Droombos Estate has become synonymous with refined hospitality and

There’s a stretch of Namibia where time slows to the gentle rhythm of river flow – where the land hums

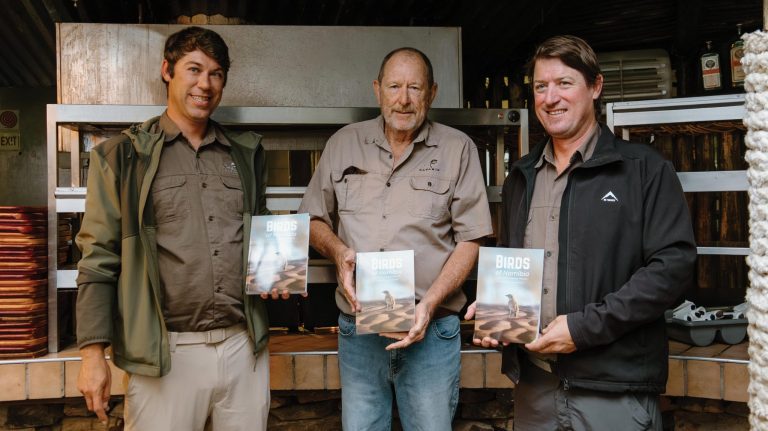

In a country defined by vast horizons and staggering biodiversity, Birds of Namibia – A Photographic Field Guide emerges as

Just minutes from Windhoek and yet worlds away from its pace, Droombos Estate has become synonymous with refined hospitality and

There’s a stretch of Namibia where time slows to the gentle rhythm of river flow – where the land hums

In a country defined by vast horizons and staggering biodiversity, Birds of Namibia – A Photographic Field Guide emerges as