Droombos Estate

Just minutes from Windhoek and yet worlds away from its pace, Droombos Estate has become synonymous with refined hospitality and

stories of glitter and glory, light and shadow

Text DELIA MAGG-THESENVITZ

It’s one of humanity’s greatest dreams: to be in the right place at the right time and make a fortune. In 1908, this dream came true for one man and some of his fellows. His name was August Stauch, a German citizen who found diamonds in the Namib Desert and turned his discovery into a fortune. While he was not the first person to pick up a diamond in that area, Stauch’s name became synonymous with the birth of Namibia’s diamond industry — one of the biggest contributors to Namibia’s GDP to this day.

Stauch’s story is not merely one of glitter and glory. It is a story of how “luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity,” and it unfolded during the not-so-glorious years of the German colonial era — the backdrop to why Germans and other white settlers were the ones who collected the diamonds and considered them their own.

The land known today as Namibia was one of the last regions on the African continent to be colonised. Although the first Europeans left a footprint in 1487 during a brief stopover, for centuries thereafter the land north of the Cape Colony held little interest — too vast, too dry, too remote, and too difficult to access. The arid region known as Namaqualand was inhabited by the Nama, Damara, San, and Herero peoples, who lived a semi-nomadic life with livestock, supplemented by hunting during hard times.

It was only in the 19th century that a handful of white men began to show interest and travel or settle there. They were explorers, missionaries, big-game hunters, whalers, guano workers, prospectors, traders, and merchants. The first white person to settle in Angra Pequena (today Lüderitz) is said to have been David Radford, whose descendants still live in Lüderitz today — some of them working as tour guides.

Stauch’s story is not merely one of glitter and glory. It is a story of how “luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity.

The white missionaries, traders, and the so-called Orlam (of the Nama tribe), who had migrated from the Cape Colony, brought with them new ways of living. Alongside cultural novelties such as Christian names, European clothing, square houses, and agriculture, they also introduced new forms of conflict — now fought on horseback and with rifles — which shifted the balance of power.

The event that set Namaqualand on the path to becoming a colony occurred in 1883, when a man with big ambitions entered the scene: Adolf Lüderitz, a merchant from Bremen whose dubious land deals marked the beginning of what would later become German South West Africa.

Lüderitz dreamt big — of a trading post at Angra Pequena, mineral mining inland, a harbour, settlements, and green gardens along the Orange River. He brought in equipment and experts from Germany to explore the land from Angra Pequena inland as far as Aus and even the Orange River. Ironically, Lüderitz’s prospectors never found any valuable minerals. This financial disaster forced Lüderitz to sell his land to the German Colonial Society (Deutsche Kolonialgesellschaft), a Germany-based organisation that promoted colonial interests in other territories as well.

Unlike colonies primarily used for crop production, German South West Africa was declared a settler colony — intended to attract Germans willing to migrate to Africa to build new lives. The fact that the land was already inhabited by native peoples was of little concern to the imperialists.

“Developing” the country, however, proved difficult. Farming was hard, infrastructure costly, and years of conflict with the indigenous people — particularly the Nama and Herero — culminated in the 1904 genocide, which claimed thousands of lives. Only in 1908 did the fighting end, and the Schutztruppe began returning home, leaving shops, bars, and hotels without customers. Economic decline seemed inevitable.

Then, in April, a miracle happened: diamonds were found. The lucky man was August Stauch, from a small town in Germany. Suffering from a lung disease, he had requested a transfer to Africa’s warm, dry climate, where his company was building railways. Career-wise, this was a setback; his new position was far less glamorous than his title, Bahnmeister in Kolmannskuppe, suggested.

Kolmannskuppe was little more than a railway siding in the desert, about 14 km from Lüderitzbucht. No passengers ever boarded or alighted there — its sole purpose was Stauch’s task: keeping the tracks free of sand. A lonely outpost with a small team, a few barracks, and daily sandstorms — a place many would have considered dreary and dull.

But Stauch, a man of wide interests, made the most of it. He studied the weather, rocks, and the movement of the dunes. He also had a good relationship with his workers. One of them, Zacharias Lewala from the Cape Colony, would become pivotal in an event that changed the course of German South West Africa, which until then had been an unprofitable venture for the German Empire.

One day, Lewala noticed something glinting on his shovel — convinced it was a diamond. He had found it in a place already searched by Lüderitz’s experts and crossed by countless explorers, traders, railwaymen, and soldiers. Nobody believed diamonds could exist there.

It would have been easy for Stauch to dismiss the claim — as others had done before — but he didn’t. He believed Lewala, entertained the possibility, and investigated further. People laughed at him, called him a fool. But he kept a cool head, secured a mining licence, gathered equipment and a small team. To his wife and children, still in Germany, he sent a simple letter with a few diamonds enclosed and a note: “Come to Africa. We are rich!”

When the news broke, a diamond rush erupted. “Everyone who still had some savings bought one or more prospecting permits, borrowed or bought a horse or donkey, and rode out into the desert. Within days, the whole area was marked with prospecting posts, resembling a sprawling cemetery,” recalled Max Ewald Baericke, a white settler of the time, in his memoirs.

The chaos of unregulated amateur mining lasted only a few months before the German government restricted the area (Sperrgebiet) and introduced strict diamond-trade regulations. What they did not realise in 1908 was that they had also inadvertently created one of the largest protected areas in the world — where the surrounding nature has remained largely undisturbed for over a century.

As new deposits were found, mining operations expanded, and towns grew. Houses, schools, hospitals, bowling alleys, even theatres and one of Africa’s first cinemas were built. Caviar and ice were brought into the desert, and the continent’s first X-ray machine was installed — not for medicine, but to detect diamond smugglers.

Many stories of that era — of luxury and innovation — still captivate thousands of tourists who visit the ghost towns of Kolmannskuppe and Elizabeth Bay. After the mines were exhausted and the last inhabitants left, the desert reclaimed the area, with sand dunes steadily engulfing the buildings. Tourists now visit not only for the stories but also for the hauntingly beautiful photo opportunities.

Yet for all the light, there were shadows. For many Namibians, these places symbolise not glamour but exploitation — a painful reminder that for decades, their diamonds made others rich.

After World War I, Germany lost its colonies. From 1915 until Namibia’s independence in 1990, the mining industry was under South African administration. Today, Namibia’s diamond industry is a joint venture, with 50 percent state ownership. Most of the country’s diamonds are mined from the Atlantic seabed, and many are now polished locally before being exported worldwide.

Namibia’s diamonds are not only vital to the economy — they have also made the country a sought-after destination for lovebirds seeking proposals and weddings. The “Namibian Sun” is a unique diamond cut available only in Namibia. Since 2024, natural Namibian diamonds can be purchased in Kolmannskuppe — and, of course, from local jewellers. TN

Born and raised on the Isle of Rügen in Germany, Delia has been living in Namibia since 2012. She is an entrepreneur and the publisher of the book “Ein Karat zu Zwanzig Mark. Wahre Geschichten aus der Zeit des Diamantenrauschs in Deutsch Südwest-Afrika”.

Just minutes from Windhoek and yet worlds away from its pace, Droombos Estate has become synonymous with refined hospitality and

There’s a stretch of Namibia where time slows to the gentle rhythm of river flow – where the land hums

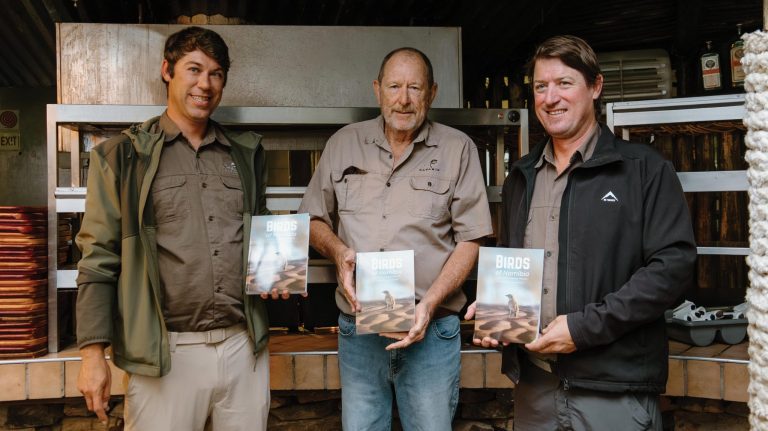

In a country defined by vast horizons and staggering biodiversity, Birds of Namibia – A Photographic Field Guide emerges as

Just minutes from Windhoek and yet worlds away from its pace, Droombos Estate has become synonymous with refined hospitality and

There’s a stretch of Namibia where time slows to the gentle rhythm of river flow – where the land hums

In a country defined by vast horizons and staggering biodiversity, Birds of Namibia – A Photographic Field Guide emerges as